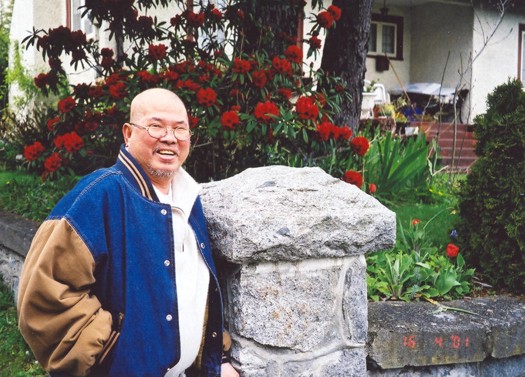

Grandmaster Remy A. Presas

December 19th, 1936 to August 28th, 2001

by Jordan Dellabough

The above picture was

taken on April 16, 2001. It was a beautiful spring day in Victoria, BC Canada when

Professor Presas, as many refered to him, was out for a beautiful walk down to the ocean

and back. He paused for a moment to catch his breathe by this post and ask," How far

did we walk today?". No matter what the answer was, Professor would always continue on and go that extra mile.

Professor Presas was

a man that openly shared his heart. His charismatic smile and

vibrant energy, which he gave so freely, touched thousands of students around the

world. Not only could he pass on his Martial Art with such enthusiasm and electrifying energy but he had this

ability to warm the hearts, inspire and bring smiles to those that came in

touch with him. His polite phrase," Can you do "dat" for

me?" will always reverberate in the ears of those he trained and remember him.

To come across a man with

an undying devotion to help people succeed in life, encourage and believe

in them, is a gift and an honour. It is also an intricate detail he

included in the "art-within-the-art" Modern Arnis. The fire he lit

stays burning, bringing warmth to students (new & old) and sparks for the

Instructors to continue to go that extra mile.

The Creator of Modern Arnis

by Jeffrey J. Delaney

For more than 50 years, Remy Amador

Presas has pursued his passion for the stick, knife, sword, dagger and

empty hand - all in the name of Modern Arnis, the Philippine martial art

he created and continues to refine. Modern Arnis is one of the most

popular, efficient and easy to learn systems of self-defense in the world,

and Presas spread the style by conducting seminars and

workshops around the globe. In fact, the humble master is responsible for

pioneering the martial arts seminar by teaching his art to students of any

style or level, as long as they are willing to pick up a stick and open

their mind.

Presas began his study of Arnis at age

6. He learned from his father, Jose Presas, in the small fishing village

of Hinigarin, Negros Occidental, in the Philippines. He left home at age

14 so he could pursue his interest in the fighting arts practiced on the

many islands of his homeland. These arts were blends of systems from all

over the world: Thailand, China, Spain, Indonesia, Japan and India. They

had reached the islands as the people of the Philippines interacted,

traded and fought with these diverse nations. Presas refined and blended

the important aspects of tjakele, arnis de mano, karate, jujitsu and dumog

into the art he named Modern Arnis. "Long ago, Arnis was a dying art,"

Presas says. "The old practitioners believed the cane was sacred. This

meant they would always aim at the hand of their training partner and not

at the cane for practice. Most of the students got hurt right away and

immediately lost interest. I modernized this and promoted hitting the cane

instead for practice. Then I identified the basic concepts of the many

Filipino systems I had learned to bring a unity to the diverse systems of

my country. This way, we could all feel the connection."

Presas prefers to use the term "arnis"

over the term "kali". "In the west, you hear the words kali and escrima

used a lot," he says. "These terms mean basically the same thing, but

if you say kali or escrima, not many people in the Philippines will know

what you are talking about. Arnis best reflects the Philippine culture

because it is a Tagalog word." Tagalog is the national language of the

Philippines.

"In the Philippines," Presas continues,

"if someone heard you were a good arnis player, they would challenge you -

anywhere. I did challenging also. We fought in the streets, alleys, parks

- all kinds of places. Sometimes there were very bad injuries, but I did

not lose."

Presas' experience and prowess were

unsurpassed. By 1970 he had created a sensation in his country. His Modern

Arnis Federation of the Philippines boasted more than 40,000 members. In

1975 he left the Philippines on a goodwill tour sponsored by the

government to spread Modern Arnis around the globe. After arriving in the

United States the art has grown rapidly.

Modern Arnis is often referred to as

"the art within the art." The techniques are based on patterns and

theories of movement, instead of static moves and drills. Rather than

learning complex forms and one-step sparring drills for each weapon,

students learn the fundamentals of natural movement and use the same

patterns of attack and defense in response to each direction, type and

intensity of attack. This is true regardless of whether they are holding a

sword, dagger, stick or no weapon at all. In addition, all the techniques

lead into a countless variety of disarms, throws and locks using the

maximum leverage available from whatever weapon is being utilized.

At the advanced level, patterns give

way to a continuation of movement. This facet of the art is often referred

to as the "flow". Flowing refers to the way in which arnis practitioners

transition effortlessly from one technique to the next as they sense the

movements and attacks of their opponent and respond automatically and

continuously.

This sensitivity is developed through a

freeform sparring exercise called "tapi-tapi". It is a technique similar to

the chi sao (sticky hand) drills of wing chun kung fu and the push-hand

training of tai chi chuan. Tapi-tapi proceeds at a lightning pace, with

sweeping strikes and blocks followed by parries, punyo (but end of the

stick) strikes, grabs, releases, traps and eventually disarms, takedowns

and submissions. This type of sparing is beautiful to watch, especially

when someone as skilled as Presas bests the most advanced opponents while

barely glancing in their direction.

"The techniques must be practiced

slowly at first," Presas insists. "That way, they will become automatic.

Also, the student must be relaxed and keep all movements small and

purposeful."

Modern Arnis teaches students to become

proficient and comfortable in all ranges of combat. Each one of the 12

striking angles that define the system has a basic block, disarm and

counter to the disarm. Once these building blocks are in place, they can

be applied to movements known as sinawali, redonda, crossada, abanico and

others. Numerous joint locks, spinning throws and takedown techniques lead

to grappling positions with still more control and submission techniques.

In recent years, Presas has focused his

energies on running intensive training camps hosted by his students in

major cities across the United States. The camps last three to four days,

beginning at 9 a. m. and often lasting until midnight. Presas offers

apprentice, basic and advanced instructor certification, as well as belt

testing for rank within the organization.

In 1982 Presas was inducted into the

Black Belt Hall of Fame as Instructor of the Year. In 1994 he was again

honored by Black Belt as Weapons Instructor of the Year. "When I think of

how Modern Arnis has grown in the United States and around the world, I

can not help but feel proud," he says. "As I travel from seminar to

seminar, I look forward to seeing each and every student. It is their

dedication to self-improvement that is my inspiration."

Presas students, in turn, describe him

as gifted, compassionate, energizing and engaging. These endearing terms,

however, should not be confused with the savage fire that burns in his

eyes as he bears down on an opponent or with the deadly efficiency of the

techniques he taught.

In his sixties, Presas continued to

hone and add to his art while helping others do the same. Through his

association with Small Circle Jujitsu's Professor Wally Jay and pressure

point specialist George Dillman, Presas' seminars and training camps are

never lacking when it comes the sheer volume of devastating techniques

available.

"I owe a lot to Remy," Jay says. "He

helped me a lot." This phrase is repeated over and over again by martial

artists fortunate enough to have crossed paths with this legendary

fighter, teacher and master of Modern Arnis. His teaching skills, charisma

and energy are inspiring to all, and his seminars and training camps

should be added to the schedules of martial artists of all styles and

systems.